Beata Ewa Białecka | Painting Attired

20 September - 24 November 2024

Contemporary Art Gallery BWA SOKÓŁ

--vernissage:

20 September 2024 , hour 18:00

Painting Attired: Beata Ewa Białecka’s embodying of painting

“Painting Attired” is an intriguing title, as it refers not to clothes in a particular pictorial composition, but directly to the nature of the medium of painting itself. It is therefore about clearly indicating the fact that garments not only (dis-)cover the figures of saints on Beata Ewa Białecka’s canvases, but they also dress the paintings themselves, enwrapping their bodies. After all, the artist operates within the sphere in which content and form – what is portrayed and how – are inextricably entwined, going to the heart of the Christian tradition and iconography.

As Georges Didi-Huberman states, “the visual arts of Christianity […] touched the very heart of an imminence that we might qualify, with Freud, as metapsychological” and the paradox nature of a painting, as they “opened imitation to the subject of the Incarnation” and to the invention of “impossible bodies . . . in order to know something of real flesh, of our mysterious, our incomprehensible flesh.”[1]. Białecka in her art performs a complete fusion of a mimetic operation with a deliberation on the status of the medium and the relationship between the body and the painting, or more precisely, body and painting in attire.[2]. Raiments do not merely clothe the depicted figures, but they also prompt us to reflect on their relationship with the picture plane and with the body portrayed therein. The aforementioned George Didi-Huberman points to the analogous phenomenon in Gothic painting, emphasising such creative acts “in which the violent relation to the subjectile (that is, to the support) went far beyond the reproduction of a wound” because “a Gothic painter wasn’t satisfied with applying threads of red paint to represent the blood of Christ spurting from his side, but used some blunt instrument to wound the surface of the gilded sheet, and make the crimson undercoating of Armenian bole surge forth again . . . [...] For it was indeed the production of a wound in the image, an injury to the image, that was then in question. The opening and the cutting became concrete, and the actual wound presented itself frontally, cut directly facing us into the gold sheet—even if, as is often the case, the wound in the picture is represented in profile.[3]. Białecka also does not settle for the use of specific paints and for the depiction of bodies in clothes, but she attires her paintings, owing to which the dressed figures of saints make themselves present before our eyes, incarnated in the medium and through the medium.

In the background, there resonates a tradition of vesting holy images, especially those most venerated, in the so-called ‘dresses,’ most often made from precious metals and set with jewels. Those ‘dresses’ separate the saint bodies from the on-lookers, giving them an additional aura and the effect of unapproachability, and by this - distancing them from us. Białecka, on the other hand, attires her paintings in such a way that they become more accessible - touchable, tangible, balancing on the edge of corporeality that we know from our own lives and the corporeality, as it were, transcending, but still remaining for us at our fingertips. Paintings such as Advent Hodegetria, or Silver Hodegetria, both from 2009, clearly refer to that ecclesiastic tradition of applying dresses, and concurrently, play with the language of advertising and with the specificity of the cutout paper dolls for girls, where the folding tabs allow paper clothes to be put on the flat dolls, also cut out from cardboard. Similarly, it is with paintings in clothes that the artist activates so many points of reference which come from so many very different worlds.

Of colossal meaning in this context is the fact that both girls that play the role of Hodegetria are dressed – as are the children they are holding – in waistcoats decorated with embroidery: beads in the case of the Advent one, and beads with sequins in the case of the Silver Hodegetria. The painting’s ‘skin’ that became equated with the skin of these figures was thus ‘attired,’ and simultaneously pierced with a needle multiple times, which additionally reinforced the multi-layered relation between the medium of the painting and the figures portrayed on its plane. Białecka s t i t c h e d together the form and the content, the motif and the medium, into one inseparable unit, dressing both Hodegetrias in embroidered outfits. Paraphrasing the words of Didi-Huberman one can say that this is attiring the painting, a t t i r e a p p l i e d to the p a i n t i n g, and the embroidery becomes tangible, bringing into being that piece of clothing, embroidered directly on the painting’s ‘skin’ and on the skin of the figures represented – even though the garment is depicted in a pictorial composition.

And although Didi-Huberman, discussing the religious Gothic painting, indicates that those processes of equating the medium and the representation occur before our eyes, but in Białecka’s work it is impossible not to notice how other sense also take part in this interaction, though most of all, our haptic, feeling bodies. This is because embodying, and not seeing, is a non-negotiable basis for recognising pictorial forms.[4]. This is very well known to the painter of Advent Hodegetria and Silver Hodegetria, as well as such painting with such thick, decorative raised embroidery as Priestess from 2018, or Salome, from 2024.

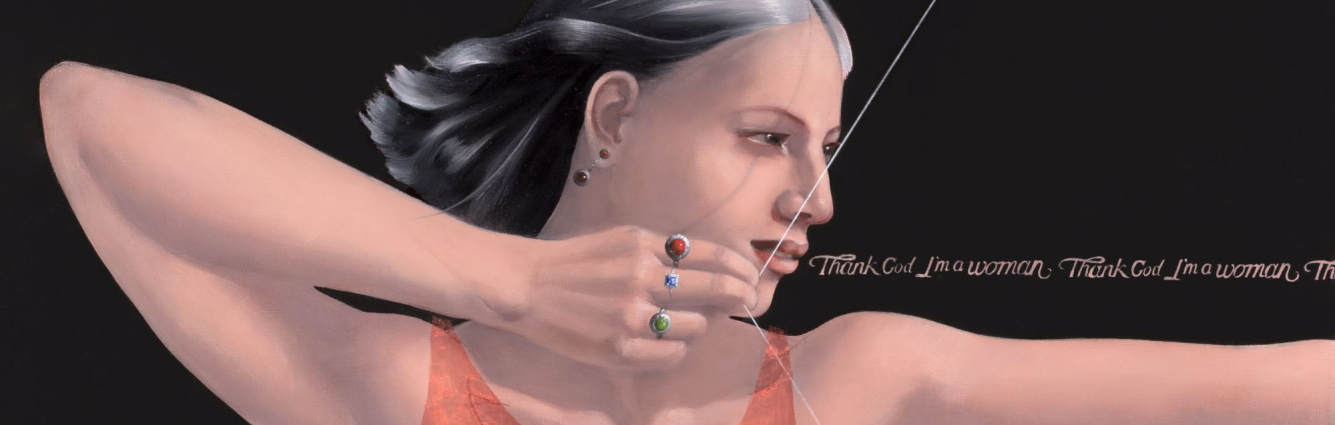

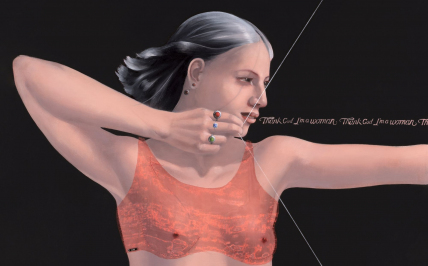

This strategy of the artist is perfectly visible in her series “Liknesses” (Konterfekty), among which there are three images of Filias, Saint Clara, and Sweet Dreams, painted between 2015 and 2018. Filias lie or levitate before us, with their eyes closed, dressed in peacock’s feathers, shiny transparent organza, laces, ribbons, and also in embroidery.

Above Clara’s twiggy arms there are embroidered roses, and across the girl’s forehead in Sweet Dreams runs a headband bedecked with little white roses in needlework. Dressed are both the depicted figures, as well as the paintings themselves. We feel this phenomenon with our entire bodies, wanting to examine the tangebility of the fabrics and the embroidery by touch, at the same time standing body to body with the attired images, which – as painted by Białecka – are more corporeal than any other representations of saints.

As Marek Prokopski stresses: “The concept of embodying cognition is a good example of a science that ignores the subjective experience of the world for the sake of abstract models, according to which cognition were to occur.[5]. In its relations to Białecka’s painting in clothes, a living body is taken into consideration in the act of the production of knowledge, and an embodied perception leads to generating senses [6]. In this context, we become not only co-feeling, but also co-knowing – before our eyes there takes place a phantasm of painting, understood – following Didi-Hubermanem – as a specific approach to the object of desire which, when attention is aroused, splits the object, and at this opportunity, also dividing the artwork itself. In the gaze, in which the transformation of the artistic medium into body takes place, we also observe and feel the attire in which not only the depicted figures, but also the paintings themselves are dressed.

Then Christine of Bolsena from 2024 – understood both as the figure of a saint, and the painting depicting her – Białecka a t t i r e s in wounds embroidered on. The artist treats them the same way as did the Gothic artists, whose strategies so moved Didi-Hubermana, namely, she cuts out holes in the plane of the canvas and covers its edge with embroidery, making an analogy between blood and open bodily tissues with red cordonette. That is the image perfectly embodied, clothed in pain, the painting which concurrently makes us co-feeling and co-knowing. As a painter, Białecka reaches the essence of immanence and of paradoxical nature of painting, a painting attired.

prof. dr habil. Marta Smolińska

Historian and Art Critic

Poznań Artistic University

Text from the exhibition catalogue, 2024

(t/r AK)

_

[1] Didi-Huberman, Georges. Confronting Images: Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art. Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005. Ch.1. The History of Art Within the Limits of Its Simple Practice. p.28

[2] Cf.: Gerhard Wolf, Das verwundete Herz – das verwundete Bild, w: Rhetorik der Leidenschaft. Zur Bildsprache der Kunst im Abendland, hrsg. von Ilsebill Barta-Friedl, Christoph Geissmar-Brandi und Naoki Satô, Hamburg und München 1999, s. 20.

[3] Georges Didi-Huberman, op.cit., p. 205.

[4] John M. Krois, Bildkörper und Körperschema, in: John M. Krois, Bildkörper und Körperschema. Schriften zur Verkörperungstheorie ikonischer Formen, Berlin 2011, p. 269.

[5] Marek Prokopski, Ciało. Od fenomenologii do kognitywistyki [Body. From Phenomenology to Cognitive Science], „Przegląd Filozoficzno-Literacki” 2011, no 4, p. 137, http://www.pfl.uw.edu.pl/index.php/pfl/article/view/567/35 (Accessed: 04 July 2024).

[6] Cf.: Johanna Platter, Teresa Margolles, and Doris Salcedo. Mitleiden. Mitwissen. Mitfühlen. Über das Moment der körperlichen Wahrnehmung in den Werken von Teresa Margolles und Doris Salcedo, Dissertation, Freiburg i. Br: modo. 2017. Platter analyses the works of Margolles and Salcedo with regard to the bodily perception, which is the source not only of co-feeling and co-suffering, but also of co-creating meanings – Mitwissen.

“Painting Attired” is an intriguing title, as it refers not to clothes in a particular pictorial composition, but directly to the nature of the medium of painting itself. It is therefore about clearly indicating the fact that garments not only (dis-)cover the figures of saints on Beata Ewa Białecka’s canvases, but they also dress the paintings themselves, enwrapping their bodies. After all, the artist operates within the sphere in which content and form – what is portrayed and how – are inextricably entwined, going to the heart of the Christian tradition and iconography.

As Georges Didi-Huberman states, “the visual arts of Christianity […] touched the very heart of an imminence that we might qualify, with Freud, as metapsychological” and the paradox nature of a painting, as they “opened imitation to the subject of the Incarnation” and to the invention of “impossible bodies . . . in order to know something of real flesh, of our mysterious, our incomprehensible flesh.”[1]. Białecka in her art performs a complete fusion of a mimetic operation with a deliberation on the status of the medium and the relationship between the body and the painting, or more precisely, body and painting in attire.[2]. Raiments do not merely clothe the depicted figures, but they also prompt us to reflect on their relationship with the picture plane and with the body portrayed therein. The aforementioned George Didi-Huberman points to the analogous phenomenon in Gothic painting, emphasising such creative acts “in which the violent relation to the subjectile (that is, to the support) went far beyond the reproduction of a wound” because “a Gothic painter wasn’t satisfied with applying threads of red paint to represent the blood of Christ spurting from his side, but used some blunt instrument to wound the surface of the gilded sheet, and make the crimson undercoating of Armenian bole surge forth again . . . [...] For it was indeed the production of a wound in the image, an injury to the image, that was then in question. The opening and the cutting became concrete, and the actual wound presented itself frontally, cut directly facing us into the gold sheet—even if, as is often the case, the wound in the picture is represented in profile.[3]. Białecka also does not settle for the use of specific paints and for the depiction of bodies in clothes, but she attires her paintings, owing to which the dressed figures of saints make themselves present before our eyes, incarnated in the medium and through the medium.

In the background, there resonates a tradition of vesting holy images, especially those most venerated, in the so-called ‘dresses,’ most often made from precious metals and set with jewels. Those ‘dresses’ separate the saint bodies from the on-lookers, giving them an additional aura and the effect of unapproachability, and by this - distancing them from us. Białecka, on the other hand, attires her paintings in such a way that they become more accessible - touchable, tangible, balancing on the edge of corporeality that we know from our own lives and the corporeality, as it were, transcending, but still remaining for us at our fingertips. Paintings such as Advent Hodegetria, or Silver Hodegetria, both from 2009, clearly refer to that ecclesiastic tradition of applying dresses, and concurrently, play with the language of advertising and with the specificity of the cutout paper dolls for girls, where the folding tabs allow paper clothes to be put on the flat dolls, also cut out from cardboard. Similarly, it is with paintings in clothes that the artist activates so many points of reference which come from so many very different worlds.

Of colossal meaning in this context is the fact that both girls that play the role of Hodegetria are dressed – as are the children they are holding – in waistcoats decorated with embroidery: beads in the case of the Advent one, and beads with sequins in the case of the Silver Hodegetria. The painting’s ‘skin’ that became equated with the skin of these figures was thus ‘attired,’ and simultaneously pierced with a needle multiple times, which additionally reinforced the multi-layered relation between the medium of the painting and the figures portrayed on its plane. Białecka s t i t c h e d together the form and the content, the motif and the medium, into one inseparable unit, dressing both Hodegetrias in embroidered outfits. Paraphrasing the words of Didi-Huberman one can say that this is attiring the painting, a t t i r e a p p l i e d to the p a i n t i n g, and the embroidery becomes tangible, bringing into being that piece of clothing, embroidered directly on the painting’s ‘skin’ and on the skin of the figures represented – even though the garment is depicted in a pictorial composition.

And although Didi-Huberman, discussing the religious Gothic painting, indicates that those processes of equating the medium and the representation occur before our eyes, but in Białecka’s work it is impossible not to notice how other sense also take part in this interaction, though most of all, our haptic, feeling bodies. This is because embodying, and not seeing, is a non-negotiable basis for recognising pictorial forms.[4]. This is very well known to the painter of Advent Hodegetria and Silver Hodegetria, as well as such painting with such thick, decorative raised embroidery as Priestess from 2018, or Salome, from 2024.

This strategy of the artist is perfectly visible in her series “Liknesses” (Konterfekty), among which there are three images of Filias, Saint Clara, and Sweet Dreams, painted between 2015 and 2018. Filias lie or levitate before us, with their eyes closed, dressed in peacock’s feathers, shiny transparent organza, laces, ribbons, and also in embroidery.

Above Clara’s twiggy arms there are embroidered roses, and across the girl’s forehead in Sweet Dreams runs a headband bedecked with little white roses in needlework. Dressed are both the depicted figures, as well as the paintings themselves. We feel this phenomenon with our entire bodies, wanting to examine the tangebility of the fabrics and the embroidery by touch, at the same time standing body to body with the attired images, which – as painted by Białecka – are more corporeal than any other representations of saints.

As Marek Prokopski stresses: “The concept of embodying cognition is a good example of a science that ignores the subjective experience of the world for the sake of abstract models, according to which cognition were to occur.[5]. In its relations to Białecka’s painting in clothes, a living body is taken into consideration in the act of the production of knowledge, and an embodied perception leads to generating senses [6]. In this context, we become not only co-feeling, but also co-knowing – before our eyes there takes place a phantasm of painting, understood – following Didi-Hubermanem – as a specific approach to the object of desire which, when attention is aroused, splits the object, and at this opportunity, also dividing the artwork itself. In the gaze, in which the transformation of the artistic medium into body takes place, we also observe and feel the attire in which not only the depicted figures, but also the paintings themselves are dressed.

Then Christine of Bolsena from 2024 – understood both as the figure of a saint, and the painting depicting her – Białecka a t t i r e s in wounds embroidered on. The artist treats them the same way as did the Gothic artists, whose strategies so moved Didi-Hubermana, namely, she cuts out holes in the plane of the canvas and covers its edge with embroidery, making an analogy between blood and open bodily tissues with red cordonette. That is the image perfectly embodied, clothed in pain, the painting which concurrently makes us co-feeling and co-knowing. As a painter, Białecka reaches the essence of immanence and of paradoxical nature of painting, a painting attired.

prof. dr habil. Marta Smolińska

Historian and Art Critic

Poznań Artistic University

Text from the exhibition catalogue, 2024

(t/r AK)

_

[1] Didi-Huberman, Georges. Confronting Images: Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art. Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005. Ch.1. The History of Art Within the Limits of Its Simple Practice. p.28

[2] Cf.: Gerhard Wolf, Das verwundete Herz – das verwundete Bild, w: Rhetorik der Leidenschaft. Zur Bildsprache der Kunst im Abendland, hrsg. von Ilsebill Barta-Friedl, Christoph Geissmar-Brandi und Naoki Satô, Hamburg und München 1999, s. 20.

[3] Georges Didi-Huberman, op.cit., p. 205.

[4] John M. Krois, Bildkörper und Körperschema, in: John M. Krois, Bildkörper und Körperschema. Schriften zur Verkörperungstheorie ikonischer Formen, Berlin 2011, p. 269.

[5] Marek Prokopski, Ciało. Od fenomenologii do kognitywistyki [Body. From Phenomenology to Cognitive Science], „Przegląd Filozoficzno-Literacki” 2011, no 4, p. 137, http://www.pfl.uw.edu.pl/index.php/pfl/article/view/567/35 (Accessed: 04 July 2024).

[6] Cf.: Johanna Platter, Teresa Margolles, and Doris Salcedo. Mitleiden. Mitwissen. Mitfühlen. Über das Moment der körperlichen Wahrnehmung in den Werken von Teresa Margolles und Doris Salcedo, Dissertation, Freiburg i. Br: modo. 2017. Platter analyses the works of Margolles and Salcedo with regard to the bodily perception, which is the source not only of co-feeling and co-suffering, but also of co-creating meanings – Mitwissen.